by Allison Dupuis, JIA Museum Educator

Hollybourne Cottage is set to celebrate Historic Preservation Month this May with a whole host of new developments. The Jacobethan-style cottage was built in 1890 for the Maurice family. Charles Stewart Maurice, the patriarch, was a partner in the Union Bridge Company. His passion for his work directly translated into the design of his family’s Jekyll Island home, where a bridge-like truss helps to support the first and second floors of the house. Charles, his wife Charlotte, and their nine children were fixtures at the Jekyll Island Club for more than half a century. They hosted Christmas parties for employees, welcomed Club member families to their house, and wrote about the broader history of Jekyll Island. Notably, Hollybourne is the only Jekyll Island Club cottage whose ownership stayed within just one family.

Today, Hollybourne is the focus of a decades-long preservation effort. A four-year-long window rehabilitation project was just completed in April, thanks to volunteer, intern, and staff efforts. These groups rehabilitated each of the cottage’s windows with new wood and glass bead, restrung them with new sash cord, painted their exteriors, and oiled their interiors. Every window in the house is now operational.

Thanks to pieces and parts from Historic Resources’ historic fixture collection, one of the three original Hollybourne bathrooms is now operational as well! Volunteers, staff, and interns installed a high-tank toilet and sink. They also ran a new 100-foot waste line and fresh water line to the building. Interestingly, this is the first time that the house’s waste line has run to the sewer rather than the river. Alongside the use of the gun room and servants’ dining room as bride and groom dressing rooms, the newly functional bathroom supports the cottage’s use as an historic venue space for weddings and other special events.

Currently, the Authority’s preservation team is working on an extensive basement structural repair. The team replaced a supporting beam and two damaged joists. They will soon add a vertical support to the basement structure. While working in the basement, members of the team discovered a 1902 contractor’s signature near an electrical fixture—likely left as the Jekyll Island Club prepared for the electrification of the island in 1903.

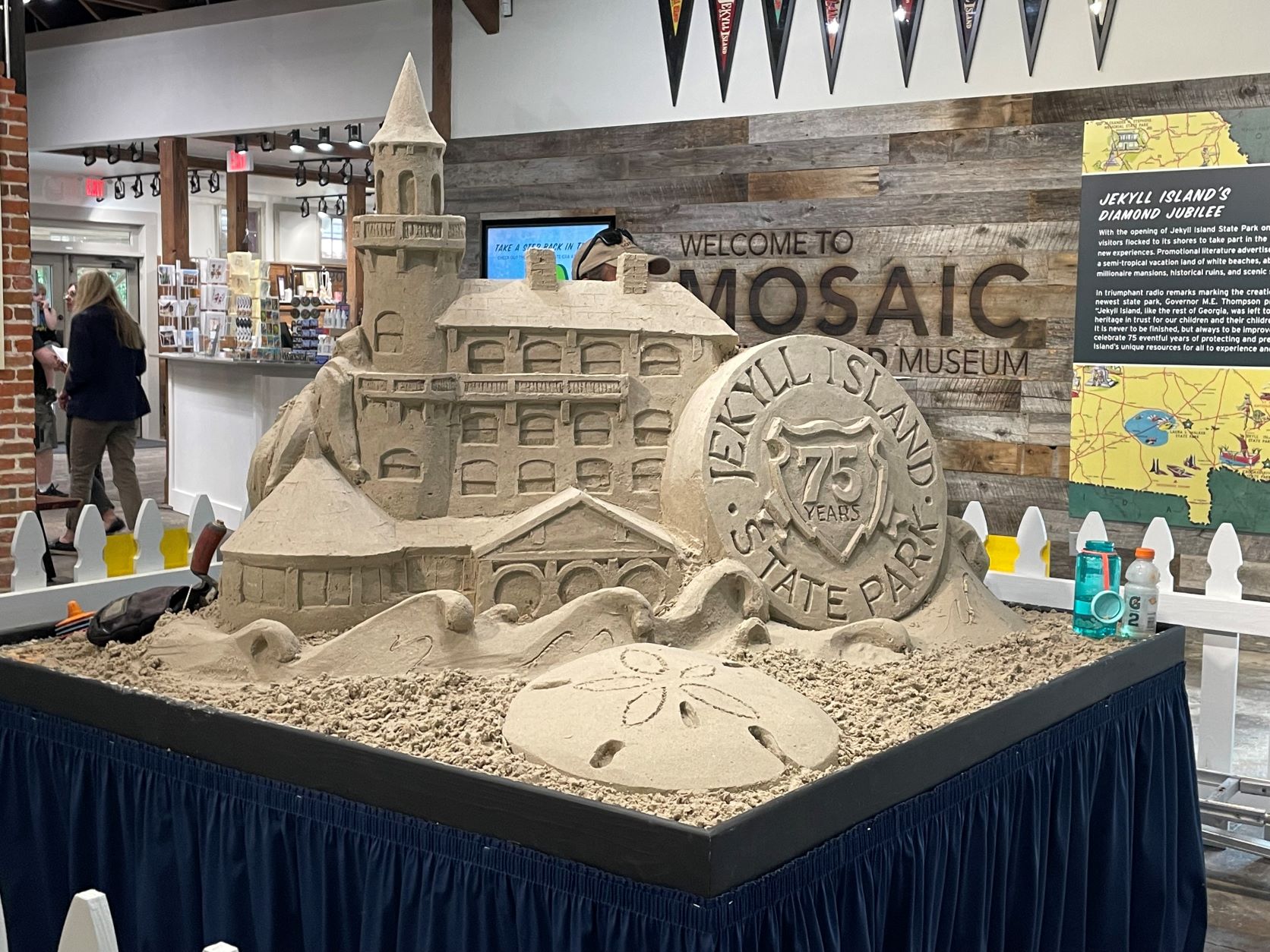

Finally, work in Hollybourne’s dining room continues. The preservation team applied finishes to the dining room’s interior. The dining room was cleaned and cleared out, while the walls were finished to exhibit level. In the cottage’s next phase, this room will house an exhibit interpreting Hollybourne’s decades-long preservation process. The rest of the cottage’s first floor will be included in the exhibit as well. While Hollybourne is an incredible and unique structure, the new exhibit will reach beyond its architecture to tell the story of the Maurice family and the house’s ongoing preservation. In the meantime, guests can join Mosaic for a daily tour of Hollybourne Cottage and see one of Jekyll Island’s most unique historic homes for themselves!