by Allison Dupuis, JIA Museum Educator

In the early 1960s, the Dolphin Club and Motor Hotel, or simply the Dolphin Club, brought hundreds of excited visitors to Jekyll Island’s shores. Nearby St. Andrews Beach had been designated the first public beach in Georgia accessible to black visitors in 1950, and in the preceding decade, the local community had worked to develop a thriving black beach resort. The Dolphin Club filled its rooms and welcomed visitors to an idyllic slice of Georgia’s coastline. It also entertained them: the Lounge was a popular entertainment venue. Under the capable management of James Chandler, the Lounge expanded its repertoire beyond local jazz ensembles and dance bands. In 1961, B.B. King performed at the Dolphin Club Lounge—and other big-name performers like Percy Sledge and Millie Jackson soon followed. The Lounge had joined a chain of venues called the Chitlin’ Circuit, which showcased black performers and catered to black audiences.

As the Lounge continued to expand its reputation, though, the Dolphin Club also began to test the limits of its capacity. In 1960, the complex and Jekyll Island itself received a request from Dr. James Clinton Wilkes, president of the Black Dental Association of Georgia, to hold the Association’s annual convention on Jekyll Island. The island could accommodate the convention-goers at the Dolphin Club but had nowhere to host a group like the Black Dental Association. Dr. Wilkes was prepared for the situation—in fact, the request was ultimately a way to force Jekyll Island to provide an adequate convention space for groups like his. Wilkes used the “separate but equal” principle to argue for the construction of a convention space within the Dolphin Club complex. Jekyll Island quickly constructed the space to hold the convention, named it the St. Andrews Auditorium, and held the convention there later the same year. But the hasty construction project wasn’t the end of the story for the St. Andrews Auditorium or for Dr. Wilkes.

Until his death in 1965, Dr. James Clinton Wilkes continued to advocate for the end of segregation in Brunswick and the Golden Isles. He and his family were featured in a documentary, “The Quiet Conflict,” that highlighted Brunswick’s journey toward desegregation. Dr. Wilkes and his family were notable both for their residence on Jekyll Island and for the birth of their youngest child, the first black child born in the “white section” of Brunswick’s hospital. The St. Andrews Auditorium continued to host larger events like family reunions and dances. In 1964, just before Jekyll Island peacefully desegregated, the St. Andrews Auditorium hosted one of its final and most famous events. Local concert promoter Charlie Cross brought the Auditorium and the Dolphin Club complex its last big-name act: Georgia native Otis Redding.

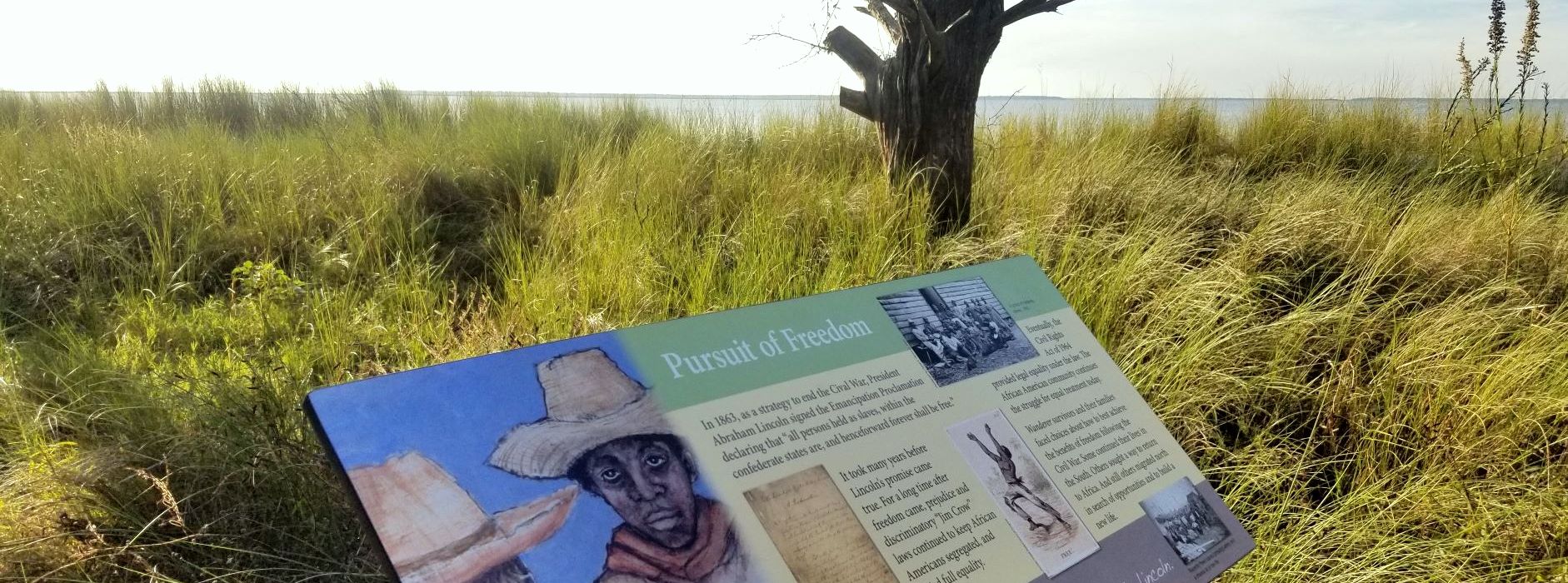

Although the St. Andrews Auditorium no longer stands, historical markers across the former Dolphin Club site stand in tribute to the building’s history and to the civil rights work of people like Dr. Wilkes. This August, Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum will spearhead an exciting oral history program that hopes to collect memories from across the island’s 75 years as a state park. If you have memories to share from visits to the Dolphin Club, the St. Andrews Auditorium, or the early state era on Jekyll, preserve them as a part of the island’s history! To learn more about sharing your memories for future generations, visit jekyllisland.com/mosaic.