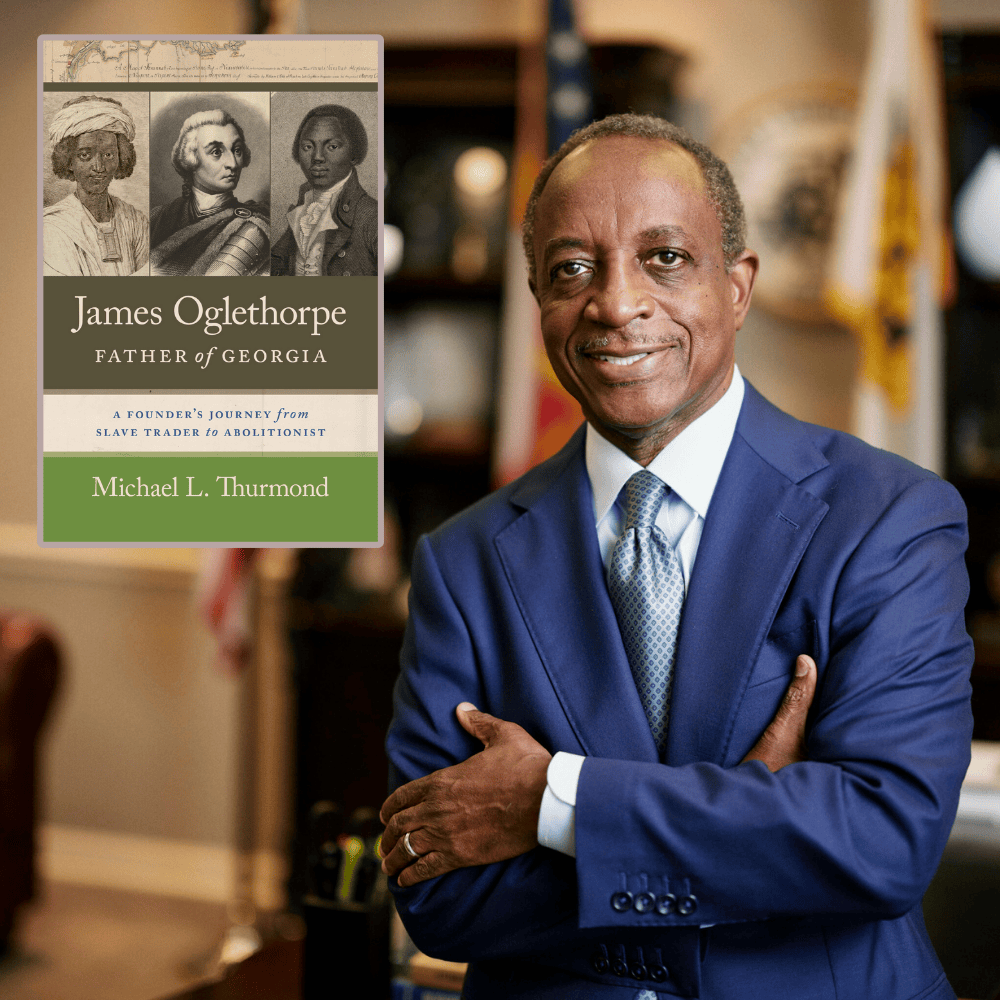

by Michael L. Thurmond

Editor’s note: Mr. Michael L. Thurmond, former CEO of DeKalb County, Georgia, is the author of: James Oglethorpe, Father of Georgia; Freedom: Georgia’s Antislavery Heritage, 1733–1865; and A Story Untold: Black Men and Women in Athens History. Read his full bio HERE.

# # #

This February/week Georgia will celebrate the 292nd anniversary of its founding by General James Oglethorpe on February 12, 1733. The Georgia colony was envisioned as a unique economic development and social welfare experiment. Administered by twenty-one original trustees, the Georgia plan offered England’s “worthy poor” an opportunity to achieve financial security by exporting goods produced on small farms.

Most significantly, Oglethorpe and his fellow trustees were convinced that widespread economic vitality could not be achieved through the exploitation of enslaved Black laborers. Later in life, Georgia’s founding father would help breathe life into the international crusade that broke the chains of British and American slavery.

Due primarily to Oglethorpe’s strident advocacy, Georgia was the only British American colony to prohibit chattel slavery prior to the American Revolutionary War. General Oglethorpe would assert that he and his fellow trustees prohibited the enslavement of Black people because it was “against the Gospel, as well as the fundamental law of England.”

The genesis of Oglethorpe’s antislavery advocacy can be traced to an extraordinary letter written by a young African Muslim named Ayuba Suleiman Diallo. In February 1730, Mandinka warriors took Diallo as a prisoner of war and sold him to British slave traders. He survived the harrowing “Middle Passage” and was enslaved on a Maryland colony tobacco plantation. Following a failed escape attempt, Diallo’s enslaver allowed the educated young man to write a letter to his father, detailing his dire circumstances.

Written in Arabic, the letter passed through the hands of several white men during its improbable 4,000-mile journey to London and it was placed in Oglethorpe’s possession. After having Diallo’s letter translated, Oglethorpe entered into an agreement to purchase the enslaved young man and pay for his passage to England.

Prior to the founding of Georgia, Oglethorpe was a member of the British Parliament and deputy governor of the Royal African Company, a British slave trading enterprise. According to a nineteenth century Georgia historian, Diallo’s “history” had a profound effect on Oglethorpe’s “ideas” regarding slavery. On December 21, 1732, Diallo’s distance benefactor abruptly severed official ties with the slaving corporation.

During the spring of 1733, while Oglethorpe was in North America, Diallo arrived in London, assumed a new name “Job Ben Solomon,” and became a “roaring lion” of British society. The budding British celebrity was emancipated by British patrons, introduced to King George II and Queen Caroline and on August 8, 1734, returned to what is modern day Senegal.

WhileDiallo was celebrating his miraculous rescue from bondage, proslavery Georgia colonists known as “Malcontents” were arguing that deteriorating economic conditions in the colony were due to the prohibition against slavery. Oglethorpe and the malcontents engaged in a divisive, unvarnished debate over the legalization of slavery in Georgia.

Georgia’s principal founder became the target of a relentless smear campaign that included claims of mismanagement and hypocrisy because of his alleged investment in a South Carolina plantation that utilized enslaved Blacks.

In January 1739, anticipating the sentiments of nineteenth century abolitionists, Oglethorpe argued that legalizing slavery would “occasion the misery of thousands in Africa…and bring into perpetual slavery the poor people who now live free there.”

Finally, on July 22, 1743, Georgia’s most strident defender of the slavery prohibition exited his beloved colony. He sailed toward a future clouded by a pending court-martial and the possibility of financial ruin. The military charges ranged from larceny to treason. Reacting to complaints from pro-slavery colonists, British officials also refused to reimburse Oglethorpe for substantial expenses he had incurred on behalf of the colony.

Although Oglethorpe was acquitted on all accounts and fully reimbursed, he never returned to Georgia. Less than a decade later, on January 1, 1751, Georgia’s slavery prohibition was repealed.

Despite the abandonment of the colony’s anti-slavery principles, Oglethorpe maintained a fatherly interest in Georgia. For the remainder of this life, the old general continued to rail against the evils of slavery. He died on June 30, 1785.

Early state historians often ridiculed Oglethorpe and his colleagues for being overly idealistic and impractical. However, contemporary Georgians should celebrate the courage and genius of Georgia’s founding father because his words and deeds are an important source of enlightenment and inspiration.

Although many of the societal ills that served as the catalyst for the founding of Georgia continue to plague our beloved state: unemployment, poverty, lack of empathy, over-crowded prisons and economic inequality. The passage of nearly three centuries has failed to dim the brilliance or lessen the significance of General James Oglethorpe’s origin vision for Georgia.