By Andrea Marroquin, JIA Curator

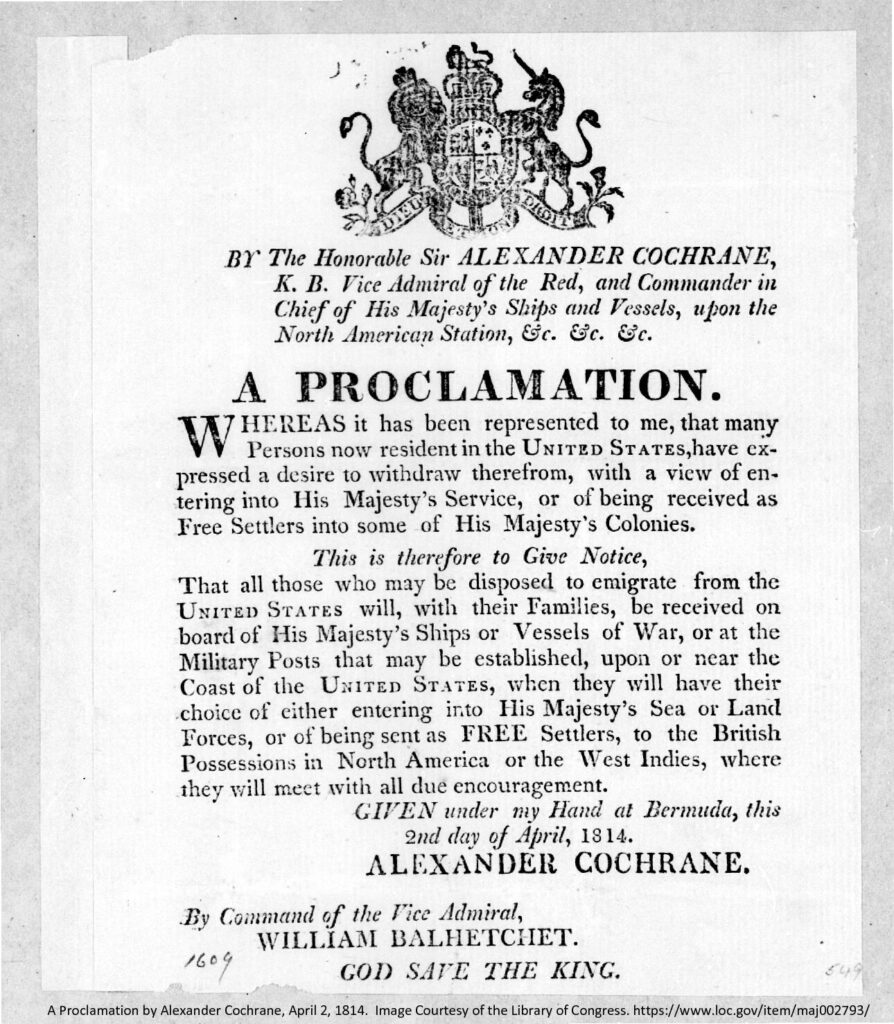

Amidst the War of 1812, a proclamation promised freedom to enslaved people who deserted to the British. This proclamation resulted in what has been called “one of the most extraordinarily effective mass military emancipations ever seen in the United States.” Thousands of African Americans are believed to have been liberated from this vicinity, including many from Jekyll Island.

British forces under the command of Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn first burned Washington D.C. and failed in an attack on Fort McHenry at Baltimore, Maryland (inspiring “The Star Spangled Banner”), before heading south. The plan was to terrorize the southeastern coast of the United States with attacks on Charleston and Savannah.

Meanwhile, the British invaded and occupied nearby Cumberland Island and conducted a series of smaller raids along the Georgia coastline. British ships attacked Jekyll Island several times, with raids continuing even after the war was already over. Christophe Dubignon later testified “my house was plundered at four different times by said British.”

One of those raids took place on November 26, 1814, when the crew of the HMS. Lacedemonian struck anchor, proceeded to Horton House, and attacked. Henry and Amelia Dubignon, Christophe’s son and daughter-in-law, later testified that the British sailors “immediately commenced plundering everything of value they could lay hands on, destroying what they could not carry off.”

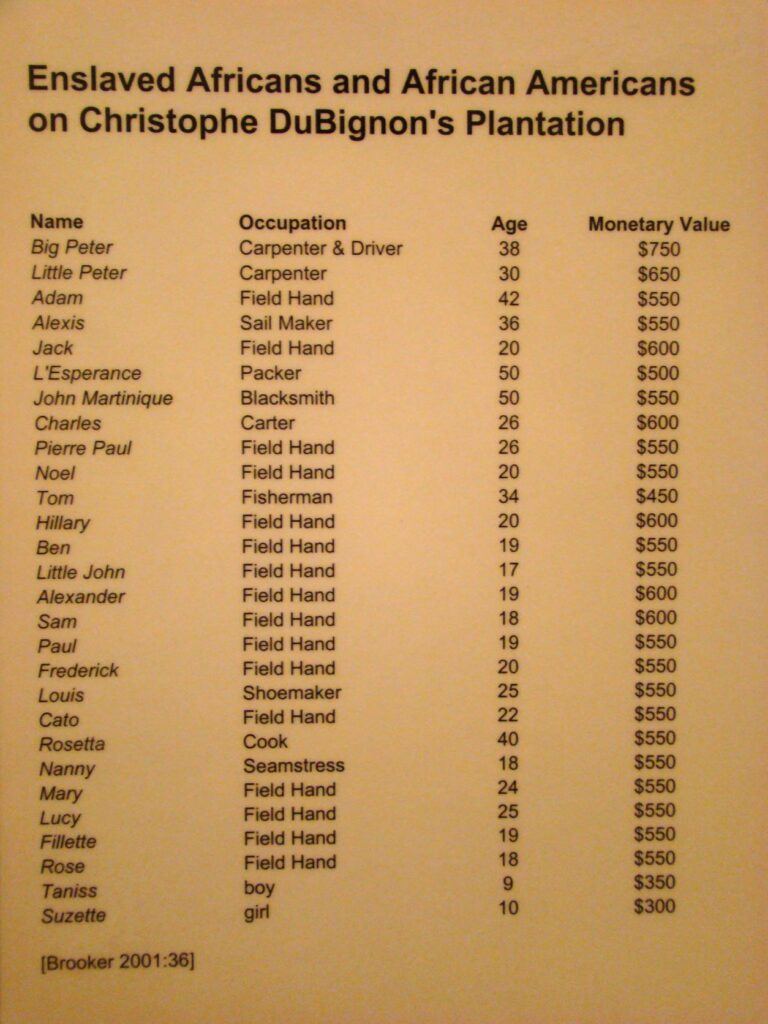

When the British departed, 28 enslaved men and women from Jekyll Island escaped with them. Christophe Dubignon documented the names, occupations, ages, and prices of the people that he complained “did desert from him.” This list included two children, sixteen field hands, and many skilled laborers, such as a carpenter, blacksmith, sailmaker, fisherman, packer, carter, shoemaker, seamstress, and cook.

Shortly after this incident, the Treaty of Ghent was signed on December 24, 1814, formally ending the War of 1812. The following March, local planters sought the return of property and slaves as required by the Treaty of Ghent. Admiral Cockburn refused to return any former slaves unless they wanted to leave. He argued that they became free the moment they arrived on British soil, and that his British ships of war qualified as such.

In April 1815, neighboring planter John Couper of St. Simons Island travelled to Bermuda “in hopes he might induce them to return.” As he boarded the frigate Brune to meet with the black refugees on board, a former Dubignon slave named Frederick cried out: “That is Mr. Couper. I wish my master was in his place. I should like to shove him down into the sea!”

Clearly, the refugees were not interested in returning to a life of slavery. Instead, they sailed to Bermuda and then on to Trinidad or to Nova Scotia, where they faced hunger and hardships but retained their freedom. Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane (Commander-in-Chief of the North American Station and Admiral Cockburn’s direct report) declared “that none of those persons have been kept in a state of slavery but suffered to go where they thought proper. . . . and those who performed any work were regularly paid for same.”

To explore more of the island’s eventful history, visit Mosaic, Jekyll Island Museum, where tours and exhibits are available daily.